Ashok Patel

Baroda, India Born 1963

-

From 03 Aug-2008 To 28 Aug-2008

-

From 05 Nov-2015 To 08 Nov-2015

-

From 01 Dec-2015 To 14 Jan-2016

-

From 11 May-2017 To 14 May-2017

Attained a Diploma in Fine Art Sculpture (1979-82) and a Post-Diploma in Fine Art Sculpture (1983-85) from the Baroda M.S. University, Gujarat; Studied Kathak dance (1997-9) and Music & Vocal studies (1981) at Baroda M.S. University

Selected Solo Exhibitions

A River flows within, Visual Art @ The Bhavan Centre (2011); 'Never alone but together', The Noble Sage, London (2008); Haymarket Theatre, Basingstoke (2007); Queen Marys College, Basingstoke (2007); Central Studio, Basingstoke (2001); The Mill Art Centre, Oxfordshire (2001); The Mill Art Centre, Oxfordshire (2000); The Nehru Centre, London (1998); Freedom from the Known, Meghraj Gallery, London (1997); Now I am Nowhere, Mandir Gallery, London (1996); The Lotus Meditation, Commonwealth Institute, London (1995-96); Sunrise Institute, Reading (1993); 1981-91 - Sculptures, Jehangir Art Gallery, Bombay (1991)

Selected Group Exhibitions

Royal College of Physicians, London (1998); Chichester Open Art Exhibition, Chichester (1997); ARKS Gallery, London (1996); Meghraj Gallery, London(1996); Gallery Space, New Delhi (1995); Chauhan Centre, Bombay (1992); Baroda Faculty of Fine Arts, Gujarat (1988)

Collections

Numerous collections in India, Japan, Belgium, Germany, Korea, UK, France and USA

Selected Bibliography & Other Media

The S.H. Daya Collection of Contemporary Indian Art by Dnyaneshwar Nadkarni, 1994

ZEE TV Programme, 1997; BBC TV Programme, 1995

Selected Awards

Artist Award (First Category), Lalit Kala Akademi, Gujarat State, 1990; Artist Award (First Category), Lalit Kala Akademi, Gujarat State, 1983

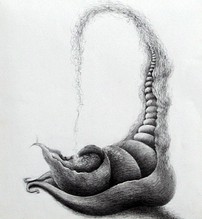

Ashok Patel's art returns us to the spiritual core of India. It leaves aside religion (which, to Patel, has now combined with the same ugliness of modern society) and concentrates on the enhancement of the soul. Normally such work would cause us to shudder with distrust and irritation. We do not like being preached to. However, the work is so austere and honest, so much about the inarticulate nature of being swept away with innate happiness (a contentment we all deep down desire), that one cannot help but listen and hope to understand and participate in some way.

Patel's artistic life began before his time studying sculpture at Baroda in the Gujarat. Although his parents did not own a single painting or sculpture, he describes his youth as engulfed in spirituality and learning. His father was a spiritual writer and singer and both his parents were Hindus open to philosophy and writings of every culture. Often Patel would spend hours with spiritual teachers and gurus learning from them ideas and concepts beyond his age that he would then follow up later in library archives. He would from a young age listen to traditional music from India, world classical music and new age musicians, attuning himself to those intangible qualities of notes, rhythms and harmonies. He says that this infrastructure of spirituality gave him power whilst his time at Baroda provided him an outlet, a means to express what he had learnt during his upbringing. Patel describes his time travelling around India before college as a great influence on him too: "There was a lot of struggle moving around India. The whole journey was an internal one as much as it was a physical trek. Although my drawing during my travels was all the time strengthening, my spiritual growth was my priority, not art." When Patel finally joined Baroda, he felt that his drawings had enough direction that learning sculpture would enable him to materialise his drawings in the real world. He specialised in sculpture but his drawings never ceased. "Drawing gave and still gives so much to me. I never depend on the sculpture. I depend on the drawing. Drawing is like an express train. It moves quickly and fluidly from place to place. Sculpture by its very nature is more permanent. In that way it is finality for my drawing though anew and different evocation for the viewer."

Patel's draughtsmanship is the product of a purer automatism. His meditative state during his drawing is so deep and honed that he himself is often surprised as to how the drawings arise: "There is no ghost operating me from within. Complex drawing takes place in a way that I cannot express. It is like I am taken. I do not conceptualise or intellectualise it. I let the energy perform. I am a mediator, a translator, I dont interfere. Between this pen and the energy I am a medium." As the artist says, his hand moves freely, creating outlines of shapes with his pencil. This early stage of the drawing can take three to four hours; the later minute detailing in contrast might take weeks or months. Both stages involve meditation, patience and a profound enjoyment of the becoming that takes place in parallel with his creating. As the artist puts it so eloquently and mysteriously: "[Art] begins when becoming is dissolved into being an experience in itself." When Patel finally views what is created he revels in its beauty and meaning to him, everyone and everything. No form such as this, he believes, could have been found by seeking it out. They come from the deepest recess of consciousness, once translated to paper, their experience transports us back into the deepest consciousness. His works are in this way the product of a communion between himself and the inarticulate, the energy that surrounds him and that is him and, indeed, is all of us too.

Pots are common symbols in Patel's work. It can intimate the body as a vessel and, indirectly, knowledge or enlightenment as a pour-able substance. Often you will see heads or bodies carved out, hollowed and made into a pouring jug or a space ready for filling. This sense of the body as intermediary space relates to the Hindu concept of the body as a vehicle for the soul, replaceable and inconsequential. Male characters in his work almost always refer to his spiritual teachers or else to himself as an embodiment of the message of these teachers. They can be spotted easily in his drawings as they have an archetypal wise old sage appearance: they have long beards and the withered look of being burdened with great knowledge. Often they are hidden, found in the outline of a pot or veiled in the wispy mark-making. "He is me in a way. I exist in the meditative process. It is not that I am wise or sage-like. But rather that I have so much association with my gurus in the world that they are inseparable. When I think of myself, I see them. When I draw them, I draw myself."

With the theme of communion is the element of circularity. The imagery within any Patel drawing often has a narrative line describing an endless energy flow from one body to another and back again. His meditative state like his pencil on the paper, is not static but progressive, moving forward, realising new dimensions of understanding and formation. Like a wheel rolling down a muddy road though, rather than taking on further dirt, relieving itself of the mud as it rolls further along the path. Such a concept of circularity clearly finds roots in Hindu philosophy of reincarnation and karma. Patel is interested in memory pattern the memories, the spiritual comprehensions, ways of living we take with us into our next lives. One might assume therefore that the tendrils and tentacles of minute pencil marks that connect one body to another in his drawings symbolically represent this transference of energy, memory, meaning and spiritual enquiry. Likewise the transfiguration, distortion and evolution of reality can be read as the visual representation of the world changed during such spiritual transference or communion.

Critic, Shivaji K. Panikkar states that 'Ashok Patel's work is a pointer to a mammoth art world in the country [India], distinct from the most avant garde artist/intellectual groups. His work is a return to India's spiritual centre, aiming to lift the soul, give hope and subtract the distrust from our lives.' Within this arena of artistic interest, it is the best of its kind. For the artist, it is the appreciation of his work that is most important. As it has been aptly put: 'His drawings and sculpture were never about the profession of art but the medium through which he continuously affirmed his search for non-identity.' His art thus is not about him. Patel is concerned only with contributing to human consciousness. Patel states: "I never claim ownership of my work because it is owned by whoever looks at it. They will get even more from it than me. They need not have created the work to gather from it its meaning. I dont have to learn the sitar to understand it. If I attune myself to the sitar I believe I can pass through the fingers of the sitarist and go further into the sound than he. I want the viewer to do the same. Treat me, the artist, as just a landmark on a journey into the work." In this soft manner, Ashok Patel is not a preacher but a bearer of an invitation, a kind invite to join him under the same banyan tree that has awarded him such shade of happiness, comfort and trust. In this cynical world, the offer is certainly alluring.